By Karilon L. Rogers

Photography by Brant Sanderlin

Just imagine taking your beloved dog – your fur baby – out for a romp at the local lake on a sun-splashed summer day only to find yourself hours later choosing between burial and cremation for your innocent companion. That’s exactly what’s happened in recent years to dog owners across the nation, from Florida to Texas and from California to North Carolina and Georgia.

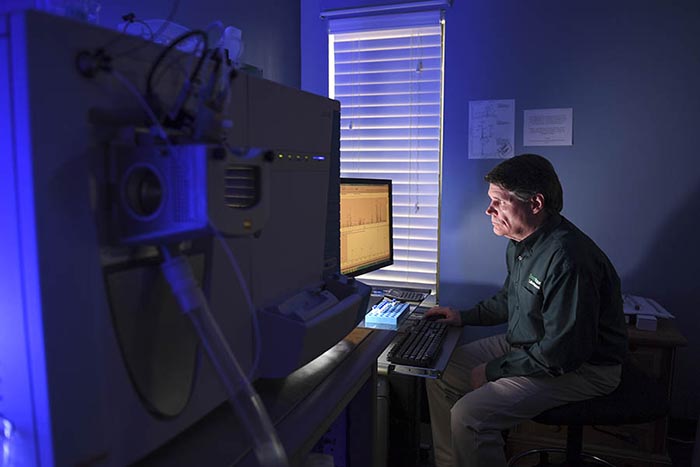

Although not proved in all cases, the suspected killer is an ancient one: cyanotoxins produced by blue-green algae. Despite the advanced age of these microscopic murderers, the body of science surrounding them is extremely limited, as are laboratories capable of rapid identification and analysis. The original – and one of the most respected – is GreenWater Laboratories/CyanoLab in Palatka, Fla., owned by Mark Aubel (81C), an analytical chemist who also serves as company president.

"Blue-green algae isn’t algae.

It looks like algae and acts like algae...

It’s actually bacteria – which often

produces one or more cyanotoxins."

“When GreenWater was started as a new venture by our parent company in 2001, it was the only private lab in the country that did this kind of work,” Aubel related. “I was able to purchase the lab in 2005, and a combination of factors has led to a marked increase in business. There has been an increase in harmful blue-green algae blooms (HAB) and in public awareness, and both have led to an increase in state and federal agencies needing to deal with the problems these blooms can bring, particularly over the last 10 years.”

Aubel’s lab has worked with such federal agencies as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Geologic Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Forestry Service and Environmental Protection Agency, as well as agencies and municipalities of more than 20 states and many private clients. The lab also provides services internationally, with clients in Europe, Central and South America, the Middle East, China, and Canada.

His team is small – only seven in all – but is extremely adept at confirming the presence of blue-green algae and then rapidly identifying any specific toxins produced in the water, normally within 24 hours. The staff also handles the culture, harvesting and purification of cyanotoxins for diagnostic and research purposes, the ‘CyanoLab’ end of the company’s business.

“I can’t overstate the quality of the people who work here,” Aubel said. “For example, our senior phycologist, Andy Chapman, is one of the best in the world at identifying types of algae, and Amanda Foss, a chemist and toxicologist, is currently providing some authorship to the upcoming revised edition of a World Health Organization publication on toxic blue-green algae in water.”

Samples of collected cyanotoxins.

What you need to know

Blue-green algae isn’t algae. It looks like algae and acts like algae, forming that disgusting, thick green layer of scum on stagnant or slow-moving areas of water. It’s actually bacteria – cyanobacteria to be specific – which often produces one or more cyanotoxins.

These toxins fall into three main groups based on what they damage – liver, skin or nerve cells. But some can be harmful in more ways than one. Microcystin, the most commonly found toxin, causes liver damage but also is harmful to the kidneys and is a possible cause of cancer.

Dogs are most at-risk because they are much less discriminating than humans about the type of water they find attractive to leap into and what slime-ridden object they might emerge with in their mouths. Also, when they swim and play, they tend to drink the water and then lick whatever is on their fur or paws when they emerge. And even if the body of water doesn’t appear to have algae on its surface, the killer could be lurking below, attaching to Fido’s fur to be licked later.

According to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, symptoms of toxicity in dogs include seizures, panting, excessive drooling, respiratory failure, diarrhea, disorientation, vomiting, liver failure and death. If your dog has been near suspicious water and exhibits any of these symptoms, get him or her to a vet immediately.

Not a pet owner?

So, why does all this matter if you don’t own pets? Because cyanotoxins don’t just affect animals swimming in algae-infested lakes and rivers; they also can invade municipal water supplies.

In the summer of 2018, for example, cyanotoxins in the drinking water of Salem, Ore., rose above EPA health advisory levels for vulnerable populations, including small children. Drinking water advisories were issued first for five days and soon after for nearly a month, but that was just part of the problem.

“All industries using Salem’s water for food production also had to test for the safety of their products – from frozen dinner companies to soy sauce production,” explained Aubel, whose laboratory played a major role in helping the city and its water-using industries recover. “Soy sauce was the most difficult for us to test, but we also were inundated with maraschino cherries. We had jars everywhere!”

There have been more serious cyanotoxin disasters in other countries. In 1996, 46 people died in Brazil when improperly filtered, microcystin-tainted water was used in their dialysis center in the town of Caruaru. Because of the safety standards in place in the U.S., such an event should never happen here.

Should you be afraid?

Experts agree that HABs are increasing due to fertilizers and untreated sewage entering water systems, as well as drought and rising temperatures, but Aubel believes that, with monitoring and knowledge, the ability to keep people and animals safe can be relatively straightforward and undemanding. Monitoring for public water-supply safety has expanded exponentially in recent years, and any toxins identified in drinking water systems can be eliminated.

And you need not fear all algae on ponds and rivers, but it is a good idea to use your head about where you choose to swim.

“People should use common sense,” Aubel emphasized. “If it looks pretty bad, I would say avoid it, particularly with your animals. As for people, we worry about young children and those who are health-compromised.”

Looking to the future

Aubel and his team are on the cutting edge of research about microcystin toxicity in dogs, beginning to work extensively with veterinarians and veterinary schools across the nation. His 2019 paper, Diagnosing Microcystin Intoxication of Canines: Clinicopathological Indications, Pathological Characteristics, and Analytical Detection in Postmortem and Antemortem Samples, looked at six dogs exposed in 2018 to a HAB in Martin County, Fla. One of the animals died, but five lived.

The study proved that all had been sickened by microcystin and provided a unique opportunity to acquire samples from living patients. Results demonstrated not only that the toxin remained in the animals for an extended period, but also that urine tests, not blood tests, revealed the highest toxin levels.

“We are looking to define a matrix for exposure that is not post-mortem and found that urine is better than blood,” Aubel stated, sharing also that these results may have an impact on human medicine: “The CDC is currently looking at blood, so our work may affect what they choose to do.”

Analytical chemist by default and at heart

Born and raised in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Mark Aubel grew up hearing about Berry. His mother, Martha Perkins Aubel (48C), is an alum, as are several other relatives. “I had scholarship offers from other schools and nothing but work opportunity at Berry, but I chose Berry,” he stated. “I played the piano, and Stan Pethel (now professor of music emeritus) probably sealed the deal. He was into electronic music at the time, and I took a one-hour composition class with him every quarter for four years.”

Aubel said he became a chemistry major at Berry “by default” but went on to earn a Ph.D. in analytical chemistry at the University of Georgia. He then did a post-doctorate at Oak Ridge National Laboratory/University of Tennessee and worked for 12 years as a research scientist in the Florida paper industry before moving to GreenWater Labs in 2002.

“I was an analytical chemist at heart and became frustrated in the corporate world as I was unable to buy the instrumentation I needed,” Aubel said. “At GreenWater, I was able to build the analytical end from the ground up: Cyanotoxin qualitative and quantitative work utilizes liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry.

“In fact, it was not until this job that I could say, ‘This is what it is all about.’ That’s why I now tell interns and graduate students who come to work with us, ‘It’s a journey. Don’t get too frustrated. If you’re not happy with what you’re doing, continue to look.’”

Today, Aubel and wife Lee, whom he married in 1987, live on the St. John’s riverfront, and when he’s not working, you’ll find him fishing or visiting with his parents, who are now in their 90s and live nearby.

He is adamant when he talks about his alma mater. The word he chooses is “proud.”

“I am proud to be an alum,” he declared. “I am proud of what Berry stands for. I have my degree and pictures of the Ford Buildings on my office wall, and I’m proud to show people where I went to college.”

And the chemistry major “by default” emphasized: “I’m proud of the academic foundation I had when I moved on to UGA for my Ph.D.