As the fall semester begins, many colleges invite experts to address the biggest challenges in higher education. This year, Berry College welcomed Dr. David Yeager, psychology professor at the University of Texas at Austin and cofounder of the Texas Behavioral Science and Policy Institute, to speak on the science of motivating young people.

The Disconnect

Many well-meaning authority figures unintentionally demotivate students by taking a top-down approach: “I’m older and wiser. Listen and learn!” Yeager coined the term, “grownsplaining,” and though it may sound obvious, many adults accidentally nag and talk down to young people in an effort to share knowledge.

Using a comparison of an ineffective non-smoking campaign vs. the most effective non-smoking campaign in history, Yeager expressed how “telling” younger ages 10-25 vs. motivating them took completely different strategies.

Dignity Builds Trust

Referencing a famous non-smoking campaign, “Think, Don’t Smoke,” in his book and talk, Yeager describes how this tagline made assumptions about the 10-25 age group. By telling the target audience to think, the marketing company made the assumption that the listeners were not thinking, disrespecting them. Adding a command to the end of the tagline did not help their case. Ultimately, “Think, Don’t Smoke” was a failure. The non-smoking campaign actually increased levels of smoking in the US.

In contrast, the non-smoking campaign, “The Truth Campaign,” heavily exposed the way the tobacco industry targeted and preyed upon young people. Rather than telling young people how to think, the campaign earned young people’s respect. It suggested that, presented with the truth, young people would be motivated to stop what was happening in the tobacco industry. And that’s just what happened. Teen smoking fell from 23% to 2%. The point here? Respect builds motivation, and without it, it can be very difficult to motivate the age group.

Between the ages 10-25, it is regularly documented that people have high sensitivity to two specific areas:

- Social status (how they're perceived)

- Fear of failure (risk of embarrassment or rejection)

For parents, teachers or any mentors, showing a student respect while also watching out for these sensitivities can feel like walking in a field of land mines, especially in college. How, then, does a mentor help someone in this age group navigate starting college? How can they show respect while also offering the feedback and growth students need?

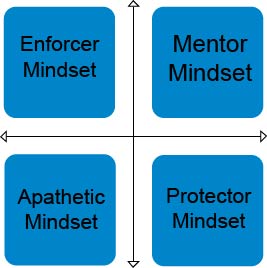

The Mentor Mindset